Life Saving Station

The U.S. Congress recognized early the importance of lighthouses to their new nation. The ninth law passed by that first Congress was creating a lighthouse establishment as a unit of the federal government. They gave the secretary of treasury authority to collect duties and maintain lighthouses, beacons and buoys. Lighthouses were first built along the eastern seaboard.

The primary reason for construction of lighthouses was to mark dangerous points along the way. It was also a means of keeping track of the steamers and other sailing vessels. Many of them sailed off into the shipping lanes and were never heard of again. The lighthouses provided a means of tracking their last known whereabouts.

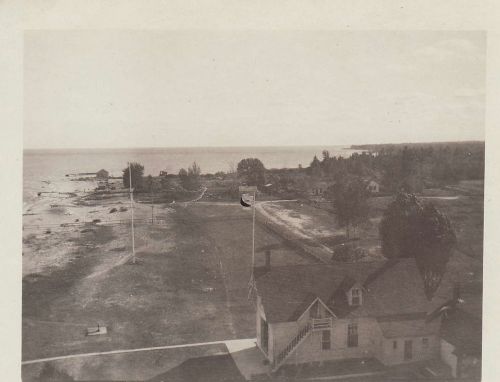

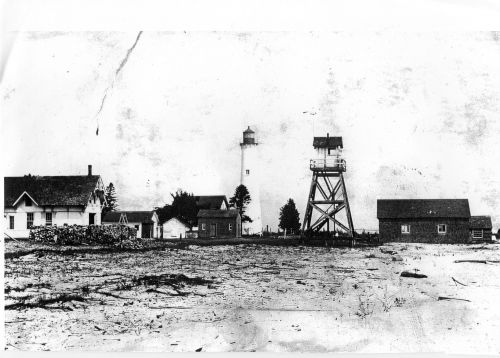

In 1866, a recommendation by the Treasury Department was made to build a lighthouse at Sturgeon Point, which was located half way between Point AuSable on the north tip of Saginaw Bay and Thunder Bay where reefs reached out one and one half miles into Lake Huron and were a menace to navigation. The area was named Sturgeon Point because during strawberry season the large sturgeon fish came up along the reefs to spawn.

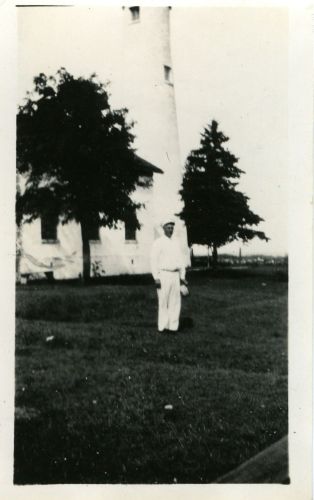

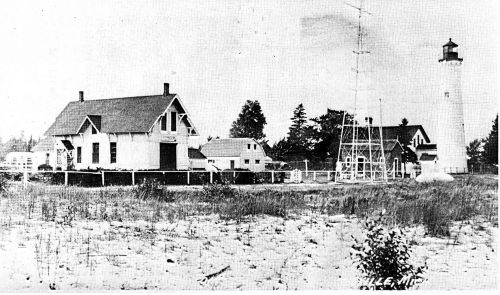

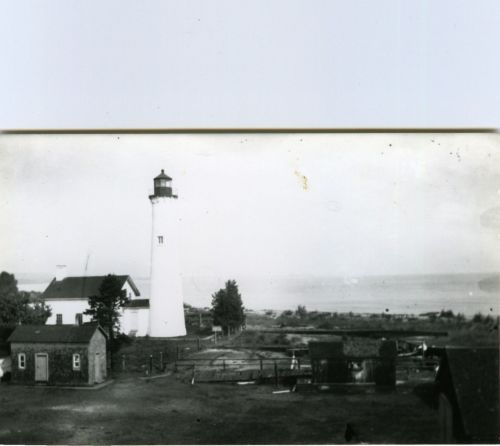

Efforts began in 1867 to secure title to the site. An appropriation of $15,000 was approved by Congress. A 60.2-acre parcel of land was purchased from John Sabin for $700 and recorded in the register of deeds records in 1868. Plans were approved July 6, 1869 and construction of the lighthouse began. The tower and residence for the keeper was constructed and that structure has remained basically unchanged to the present day. The tower is circular and built on a foundation of limestone seven- and one-half feet high, four feet below surface. Brick was used in the construction of the base which is four- and one-half feet thick. The base is 16 feet in diameter. The height of the tower, from base to the ventilator ball of the lantern, is 70 feet nine inches.

By November 1, 1869 the dwelling was covered in and the tower was ready to receive the lantern. The lantern was made by Henry LePalte of Paris, France and had been used in the lighthouse in Oswego, New York. It was attached to a cast iron base and bolted to the lantern floor. A fixed white light was installed which contained two wicks. The outside wick had a diameter of one and seven-eighths inches and the inside wick had a diameter of one and one-sixth inches. These wicks were set in the lantern which has a series of prisms and lenses. There were eight prisms in the central drum of lens. These wicks, lighted by kerosene, set in the lantern, thrust the light 16 miles out into Lake Huron.

Perley Silverthorn became the first lighthouse keeper and had the privilege of lighting the kerosene lamps. He also wound the clock. The clock mechanism was set so that the light was flashed on and off at spaced intervals.

Silverthorn had moved his family into the area in 1854. He set up a fishing station and cooper shop just north of the lighthouse property. He fished Lake Huron.

The lighthouse keeper was required to permanently reside at the lighthouse. The keeper’s dwelling was connected to the tower by an 11-foot passageway. There were eight rooms in the two-story dwelling. The first floor was divided into a kitchen, pantry and storage room. The second floor had four compartments which consisted of a sitting room and sleeping rooms.

The keeper was responsible for the care and custody of the station property and grounds. He had charge of any shipwrecked property until it was retrieved by the owner or his agent. Life was quite routine for the lightkeeper’s family at the lighthouse. The 1870 Alcona census shows the Silverthorn family consisted of Perley, 40, his wife, Caroline, 38 and their four children, Addison 12, Lydia 8, Jane 6, and May 2.

John Pasque became the keeper when Silverthorn resigned in 1876. By 1882 the lumbering industry was moving at a fast pace. Pasque decided to resign and seek his fortune in the tugging business. He moved to the Alpena area.

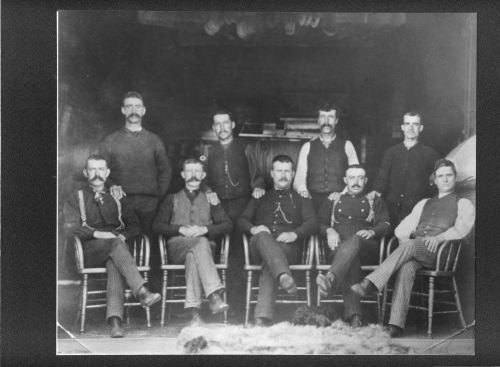

The Treasury Department appointed Louis Cardy Sr. as the lighthouse keeper. He had joined government service in 1846 when he was 17 years old. He was a member of the first crew that surveyed the Great Lakes. Cardy stayed on until 1913. In July of that year the light was changed to acetylene gas in the “no keeper class.” Cardy and his wife, Mary, remained in the keeper’s dwelling until October 1913. He resigned and they moved to their son’s home in Alpena. He died just three weeks later at the age of 84 after having served the government on the Great Lakes a total of 67 years.

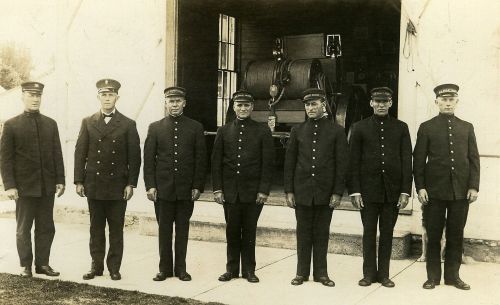

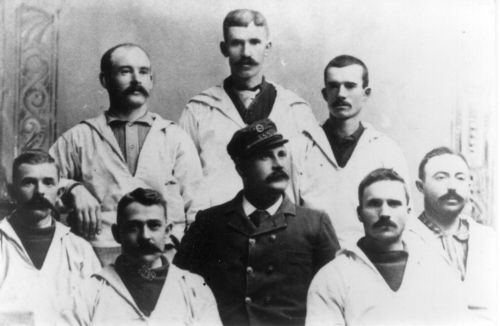

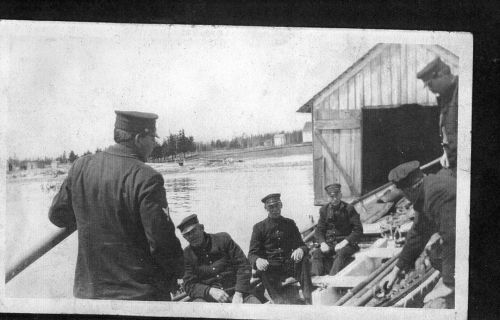

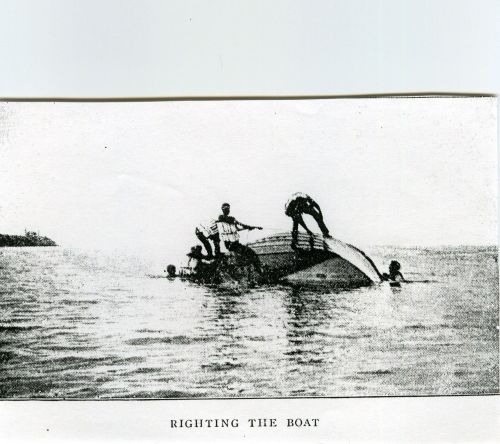

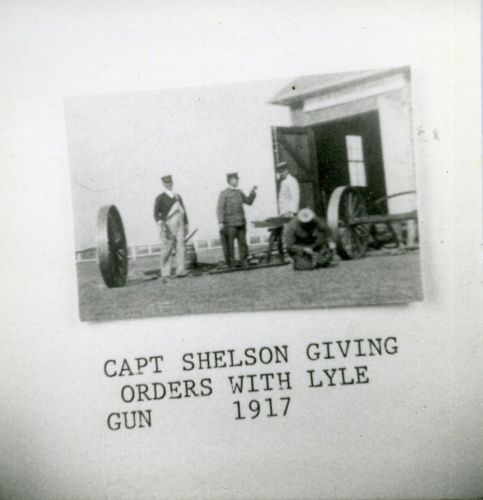

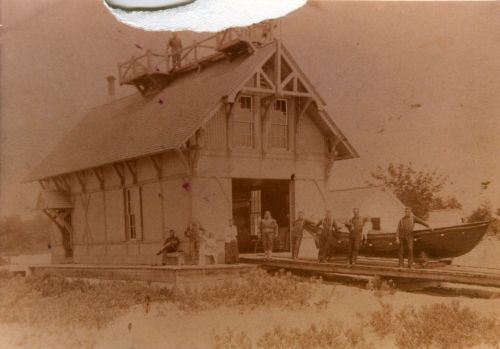

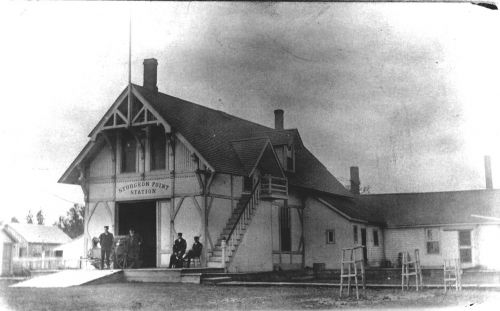

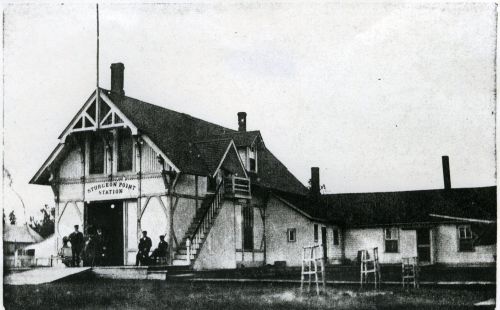

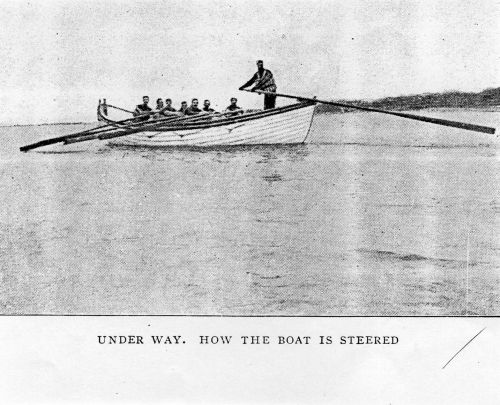

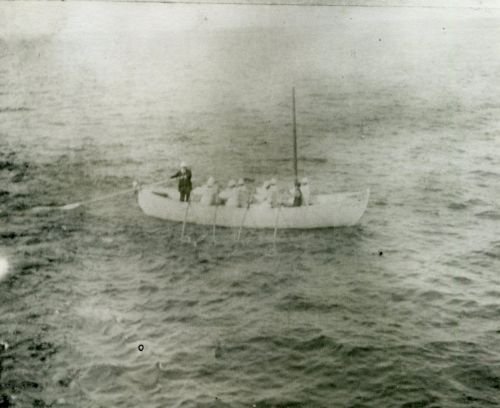

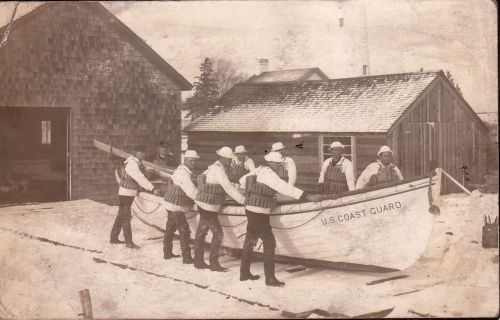

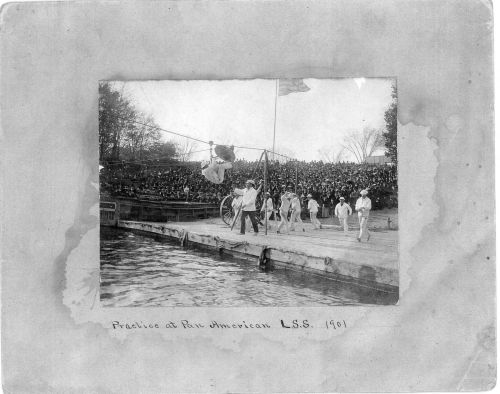

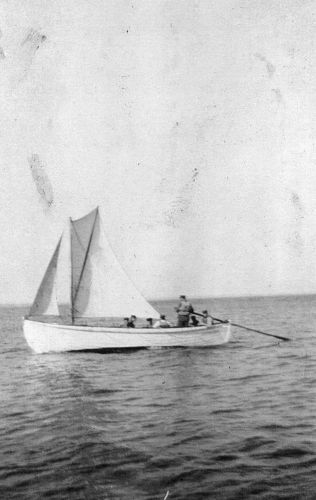

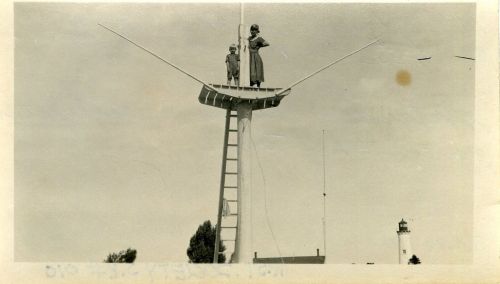

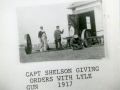

In 1876 a second service was set up on the Great Lakes — to save the lives of those who faced peril on the Great Lakes. The Sturgeon Point Lifesaving Station was built during 1876 and opened on September 15, 1876. A total of $4,790 was allocated to build a life saving tower and furnish the station with essential equipment. The equipment consisted of a surfboat and a few other pieces of apparatus. The surfboat was used at the station from 1876 to 1888. The first boat weighed 500 pounds and could be fitted with sails. It required a crew of six. In 1889 a large life boat arrived to replace the surfboat. This required a crew of eight.

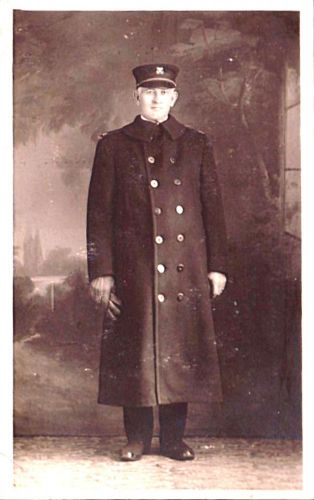

At first these life saving stations were maintained by volunteer crews. They were to receive $10 per rescue, involving the saving of human life. Perley Silverthorn became the first keeper of the station. He was paid a yearly salary of $200. He had resigned his job as lighthouse keeper, which had paid a yearly salary of $400 and had provided him a residence. It was felt the lifesaving station work would be more exciting than lighthouse keeper chores.

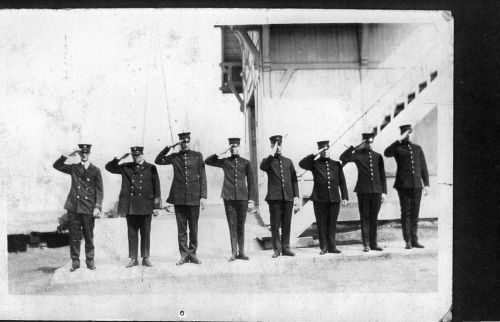

The keeper was selected by the superintendent of the district. He was required to have a thorough mastery of boat craft and surfing. He had to be able to read and write, be of good character and habits and able bodied. Another requirement was to be less than 45 years of age.

The keeper oversaw the selecting his crew. Both keepers and crew were examined by a board of inspectors comprising of an officer of the Revenue Cutter Service, a surgeon and an expert surfman.

During the first years of operation, the lifesaving station opened in the spring and continued through the end of navigation season in mid-December.

By 1937 lifesaving stations along the Great Lakes were being reduced in number and manpower because commercial vessels were a rarity and most vessels were equipped with radios. By 1941 William Olson, keeper of the lifesaving station, retired after more than 31 years of service in the U.S. Lifesaving and Coast Guard Service. The station was closed and the last remaining surfman, George Elmer, was transferred to East Tawas.

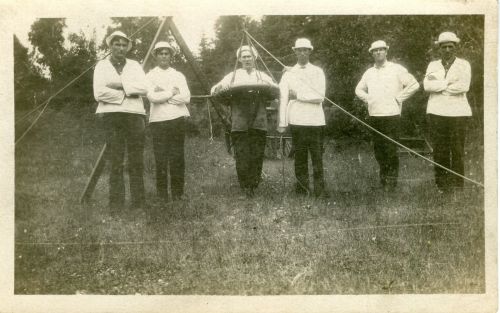

Sturgeon Point was the focus of a variety of social activities. During the summer, baseball games were played there, family picnics were a favorite pastime, and visitors could watch the drilling, take a tour of the lighthouse and climb the tower. Dancing was a favorite summer and winter pastime. The crew of the lifesaving station usually gave an annual closing ball. They would sometimes secure a building in town to hold the event. It was one of the social events of the season.

Information for this introduction was provided from Doris A. Gauthier’s book “Alcona – The Lake Pioneers.”